Flying cars are finally here. Some people call them eVTOLs (Electric Vertical Takeoff or Landing) or air taxis, and others call them flying cars.

We call them Airspeeders. What’s important is that we’re seeing the dawn of a new era and it will change the way we all move in a big way. The Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) market is expected to reached US$155 billion by 2035, according to Deloitte. Morgan Stanley has it pegged at US$1.4 trillion by 2040.

While the truth may lie in the middle, the reality is that, according to the Vertical Flight Society, there are over 600 eVTOL vehicle concepts being developed by over 350 companies worldwide right now. What’s fascinating is that much of this financial momentum has been generated by the automotive sector, who are looking to apply their transferrable technology and assembly expertise into the vertical space.

Automotive giants such as Toyota, Daimler, Porsche, Hyundai, Suzuki, Stellantis, and Geely have recognised the potential of AAM and started making their bets, either going it alone or partnership with aerospace startups.

This has resulted in the AAM industry stabling a handful of ‘flying unicorns’, private eVTOL or air taxi companies that are worth over a billion dollars. The great air taxi race has well and truly begun.

Tomorrow’s science fact

Anyone who has seen any sci-fi movie knows just how long we’ve waited for this vision to become a reality.

What has transported this vision from science fiction to reality is the convergence of a few technologies, predominantly the evolution of electric batteries, the advancement of electric motors, and the power of flight controllers and sensor systems.

The majority of the players in the industry are chasing one of two markets.

The first is cargo, with a vision towards the autonomous transportation of goods. The second, and much larger of the two, is the air taxi market. These players have a vision of cities adorned with ‘vertiports’ on top of the skyscrapers, transporting business people around town, to and from airports, and even into the suburbs, changing the way some of us commute.

Thanks to the convergence of these key technologies, these shared mobility vehicles are expected to be quieter, cheaper, more digitally enabled, safer, and more sustainable than a helicopter.

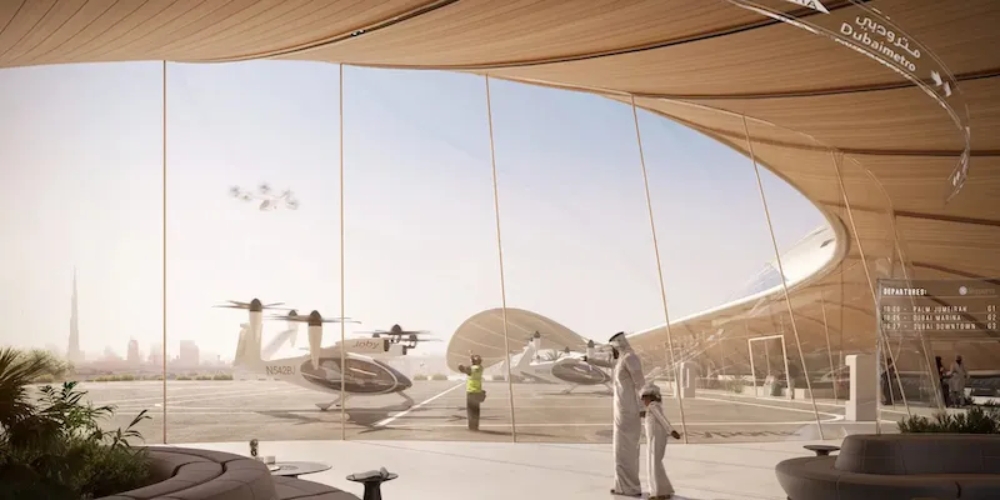

One day, they will even be autonomous. On the infrastructure side, Vertiports are coming to life in places like Dubai where Skyports and Joby have been given the green light to start development for a city-wide electric air taxi service.

Even regulation is starting to take shape. In November 2022, the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) proposed new rules that will help pave the way for commercial air taxi operations by 2025. Some of the key foundations for a major mobility revolution are starting to fall into place.

The Dubai vertiport network (Source: Skyports)

A generation-defining mobility revolution

In terms of speed, when these major mobility revolutions happen, they tend to happen very quickly. For example, in 1900, there were approximately 20 million horses and 4,000 registered automobiles across the US.

Within 20 years, there were over 20 million registered automobiles in the US, of which The Ford Motor Company was responsible for around 25 per cent, and the role of the horse in transportation had been put out to pasture.

With regards to scale, if this industry continues to boom as it has over the past six years, it has the potential to be one of the biggest shifts in mobility that we’ve seen in a generation or two.

Should the vision extend beyond shared mobility and air taxis into private ownership, then the impact of scaled AAM is an order of magnitude greater than the advancements of EVs or autonomous cars.

Its impact is more comparable to the seismic societal shifts brought on by the dawn of automobile or commercial air travel. The remaining question is how does it come to life?

Racing as a pathway

I regularly hear those in the AAM industry say it’s no longer a question of ‘if’ but a question of ‘when.’ The question I am more interested in is ‘how’, what is the first step in bringing this mobility revolution to life.

As a student of history, I wanted to look at how other major mobility revolutions have been formed in the past and I can’t help but see the parallels (and upcoming challenges) between the dawn of the automobile and vertical air mobility landscape today.

When the era of the automobile began there were no car-ready roads, no gas stations, no driver’s licenses, no DVLA, there was regulatory push back via The Locomotive Act (UK) or Red Flag legislation (US), and there was certainly no desire from the public for these big and noisy machines.

There wasn’t even agreement on the nomenclature of these brand new vehicles, with ‘Road Machine’, ‘Motor Wagon’ and ‘Quadricycle’ early front runners (all comparably better than ‘eVTOL’ in my opinion).

It was because of these technological, infrastructural and regulatory limitations, the first pure application for this new technology was racing. It was gentleman racers, racing on private tracks or competing in long distance races.

The racers themselves were names like Charles Rolls (Rolls Royce), Marcel Renault (Renault), Henry Ford (Ford), who went on to become motor dealers and manufacturers, using the money and fame from racing to build their brand, drive technical innovation and bolster their position in this new market.

Henry Ford in Michigan, 1901

This strategy has been seen time and time again, where until only recently, almost every luxury or major auto brand today can find the roots of their success in racing. Outside of building some of the world’s biggest brands, some that have lasted over 120 years, motor racing did (and still does) three things spectacularly well.

It accelerated performance technology (nothing drives innovation like competition), it fostered the advancement of safety technologies (seat belts, rear view mirror, ABS are byproducts of racing) and most importantly, it captured the imagination and affection of the public.

It allowed people to fall in love with the car. This is exactly Airspeeder’s purpose. Airspeeder has been designed to drive the same three objectives for the vertical mobility market while also giving the automotive sector a ‘space and place’ to do exactly what they did 120 years ago, just this time elevating motorsport to the skies.

Developing the infrastructure

Alongside Alauda Aeronautics, the world’s leading performance eVTOL manufacturer and Airspeeder’s sister company, we’ve designed and tested 15 Airspeeder Mk3’s, a full scale 4.3 metre-long uncrewed and remotely piloted eVTOL capable of hitting just over 88mph (without a flux capacitor).

Our Speeders have been built by a team of engineers from the aerospace world (Boeing, Airbus, Dassault), as well as Automotive (McLaren, Ferrari, Toyota) and raced by some of the world’s most talented pilots from a host of backgrounds, including former Formula One driver Bruno Senna.

I initially thought the challenge was building the vehicles and finding pilots but that was only the beginning. To take that extra step to go racing in 2022 and 2023, we challenged ourselves to create the rigorous flight and racing infrastructure necessary for close circuit racing.

This included building a bespoke track system that could design, map and implement a digital Augmented Reality Sky Track for the pilots to navigate through, Pilot Control Systems (PCS) for vehicle control, Engineering Control Systems (ECS) for team telemetry data and performance monitoring, Race Control Systems (RCS) for race and flight officials monitoring all airborne craft, ensuring race compliance, track overview and live penalty awarding systems.

This all had to be built on a customised and remotely deployable network to allow live footage from the multiple chase drones filming the sport from the air, as well as the TBs of data and onboard video streaming from the Airspeeders themselves. Not to mention, the teams had to get good at battery swaps, our version of a pit stop.

During our last two races in December, we expanded the envelope further by introducing a live broadcast team and broadcast feed on site, as well as creating a VIP hospitality zone for our key partners.

We hadn’t just built a race circuit, we built an entirely operational airport complete with a business class lounge. The technological infrastructure required for the cities of tomorrow was being regularly pushed to the limits on our racetrack today.

Final preparations for the Airspeeder EXA Series in 2023

Looking to the future

This year, the Airspeeder series has taken another step forward. Having built and tested the critical infrastructure, racing procedures and sporting elements we’re now ready to introduce the riskiest element, the crewed vehicles.

One year on from the announcement of the Airspeeder Mk4 in February 2023, our first crewed vehicles have begun initial testing in preparation for simple forms of racing this year. We also look forward to announcing our first Airspeeder teams who have been selected from the automotive OEM world because of their well-founded legacies in racing.

We’ve offered those teams a turn key solution by which Alauda will implement the team’s relevant technologies initially into a stock vehicle. Over time the teams will become increasingly responsible for technological innovation and integration, designed to allow innovation to flourish and take the series from a stock to formulaic model.

Finally, we’re excited to take the newly evolved racing product internationally, promoting the global exposure of this sport and this new form of mobility.

History repeating itself

Watching the two Airspeeder EXA series races in the Australian outback last year, where we had three Speeders racing, overtaking and undertaking each other, it struck me that we were witnesses to history being made and seeing a snapshot into the future.

Simultaneously, it all felt rather familiar as well. I could now appreciate how a spectator witnessing the Paris-Rouen motor race of 1897 might have felt, seeing the power of these new machines and getting a feeling this was going to change the world.

I can only imagine what Airspeeder will look like in 20 years’ time. To borrow a quote often attributed to William Gibson, ‘the future is already here – it’s just not very evenly distributed’.

For me, that’s what modern motorsports should be. It’s a competition where innovative cutting edge technology and machines enable drivers to safely push the limit of what’s possible.

It’s the cradle for mobility revolutions, it’s where an unevenly distributed future is showcased on a world stage in the form of entertainment and as history has shown, it’s how mobility revolutions begin.

As for Airspeeder and the new world of flying car racing, we’re just getting started.

Jack Withinshaw is part of BlackBook Motorsport’s Electric Energies Commission, an advisory group consisting of senior figures involved in shaping the future of electric motorsport. To learn more, click here.